|

Interview with Crispin Hughes

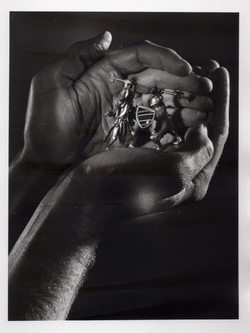

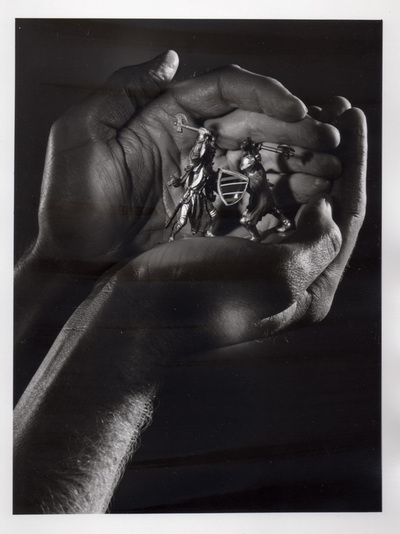

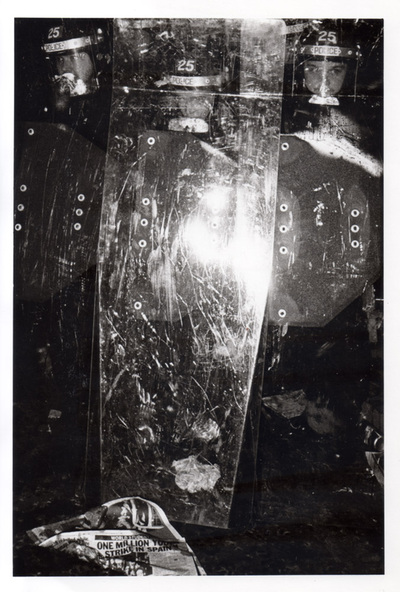

Photographer What motivated you to join the Photo Co-Op? At University I stumbled upon Camerawork magazine. My rather autistic teenage interest in Photography morphed into a political understanding of the use of photography. A year or so later I found myself apprenticed to Rajendra Shaw, a photographer based in Hyderabad using photography for social justice campaigns. On my return to the UK in 1982 a friend mentioned they'd heard of a political photography group called Photo Co-op and along I went. At that time we were just an informal group, meeting in members' houses in Tooting. Members would show work and discuss projects. From this emerged The Big Red Bus Calendar and other photo campaigns. The Photo Library originated around this time in a filing cabinet at Gina’s house. What was going on in society at the time? The Falklands war had just finished and established the 'Iron Lady' persona of Margaret Thatcher. Her sweeping privatisation agenda was affecting all aspects of civil society. Workers in transport, housing, health, and sanitation were laid off en masse and re-employed by contractors with lower wages and poor contracts. At the same time new ideas around the politics of gender, race and sexuality we're moving out from academia into the real world of politics and society at large. Thatcher won most of her battles - witness our current grotesque income differentials - but some she lost. It's now possible to be openly gay or lesbian without facing official persecution. What was the first major project you worked on? The Big Red Bus Calendar was a campaign against getting rid of conductors on London's buses. At the time fares were taken in cash. Switching to one person operation slowed down the whole system. What was the most important project you worked on and why? I ran an Images of Men photo group. I'm not quite sure why I did this. I suspect it was because I was told to by the Women's Group. Feminist women's 'consciousness raising' groups were a major feature of the new left landscape. There was a feeling that there should be an equivalent for men and I felt a vague sense of obligation. The results were surprisingly good: a naked man bursting turgidly out of a bin bag sticks in my mind. What do you think was the most important aspect of the Photo Co-op? Why did you consider it special? Photo Co-op melded new critical thinking around images and power with a real engagement in local politics. It succeeded in mixing an approachable camera club with community activism and infusing it with a feminist inspired 'personal is political' ideology. Unlike much of the academic thinking of the time it actually promoted the use of photography, rather than seeing it as merely oppressive. How do you feel the Photo Co-Op influenced what you are doing today? After spending many years working on assignments for NGOs in different countries in Africa, I have now come full circle and spend much of time doing what is clunkily called ‘participatory photography’. The thinking behind it is very similar to the Photo Co-op ethos but without the ball and chain of learning darkroom techniques. In the 80s community photography had a Marxist inspired idea that people should take control of the means of production. This meant long hours in the darkroom that could have been better spent out taking photos. The digital age has brought a new wave of opportunities for advocacy by people who would previously have been silent. I am now part of a number of projects around the world teaching local NGO workers, HIV+ve groups and schoolchildren to use photography to powerful effect. |

'Photo Co-op melded new critical thinking around images and power with a real engagement in local politics. It succeeded in mixing an approachable camera club with community activism.'

Crispin Hughes Photographer |